Best is yet to come

It is a long time, or at least it seems like it, since people stood, open-mouthed, looking in utter amazement as a strange looking machine we would now know as a wide-format inkjet printer, spat out full-colour, dry to the touch images in broad daylight. At that time, ‘big photos’ cost big money and they were, more or less, the exclusive province of expensively equipped photo-labs or high-end screen printers.

That changed. The first blob of ink ever ejected in the manner of today’s inkjet technology, so legend says, only happened because a lab technician accidentally bought an ink-filled hypodermic needle into contact with a sizzling hot soldering iron. Give thanks. They were evidently possessed of the vision to see some potential in the accident. So was born a journey of further invention and staggering onward refinement—its destination was the commercially viable thermal inkjet head, or ‘pen’ as its proud parents insisted on calling it.

Looks like an inkjet

Whether by design, or by its polar opposite, accident, very useful ink metering technologies came into being. People saw a future for the technology once it had done battle with cutting plotters and won. Encad was among the very first to press this nascent technology into something resembling a modern inkjet printer. They made pictures come out of it too, and, as we have established, that none-too-little stunt stopped people in their tracks.

The droplet that gave inkjet its development basis was uncontrollably ejected from a needle by a hot solder iron according to legend

Major revolutions though were happening elsewhere. Raster Graphics managed to get its collective brains around the delivery of proper ink, through solvent-resistant ink-train components and big arrays of piezo heads. That was, and is, a very big deal indeed. It meant you could print on the sign industry’s favourite flexible material—self-adhesive vinyl. It also meant that said vinyl did not need to be coated to receive the ink and that the print would not wash off in the first shower. It even came with the expectation of durability unlike the output from lesser print technologies which was, to exaggerate slightly, as sensitive to light as photographic film—anyone remember film?

That is, in very brief and necessarily approximate terms, how today’s print technology came into being. How the markets that print technology serves then really bloomed is a story that changes from time to time and from place to place.

Without a shadow of a doubt, 3M gets a share of the spotlight for not just commercialising Scotch Print electrostatic print hardware, but for making a market for the durable, wide-format colour output it produced. At one time, in the big boys’ end of the wide-format market pool, it was the only game but not the only thing floating—a few dismal efforts from others bobbed up and down. Eventually, natural selection took marginal technologies away and ever better inkjets came through effectively sunsetting electrostatic in the wide-format role.

Today, we rather take for granted switching on a printer and having it work. Early efforts had virtually to be raised from a coma. We take for granted too a reasonable turn of printing speed and a breathable atmosphere while the printer is doing its thing. And why should we not? The pioneers in the wide-format business took the arrows in the back for us. The kit we use today works and works well. Roland, Mimaki, HP, Epson, and the rest of you, thanks.

Today, we rather take for granted switching on a printer and having it work”

That is the hardware sorted then, now what about the materials? Way back in the day, when, as discussed above, inkjet was taking its baby steps, very grave prognostications were cast in the general direction of the sign industry’s materials market. ‘Media’ back then meant coloured self-adhesive vinyl, or ‘materials’. The cutting-plotter equipped industry would convert these materials into all manners and means of satisfying the need for signs. They were cut, painstakingly weeded, and then applied. The results looked brilliant and they still do today.

The materials manufacturing, conversion, and distribution industries seemed then to collectively look into what was a pretty cloudy crystal ball and began wailing about the coming day when sign-makers would not need coloured materials. “What was the point,” said these heralds of woe, “of having coloured materials on the shelf, if you could take but a single roll of white and print upon it any colour you wanted?” One industry giant though branded the whole unofficial movement as ‘The Charge of the White Brigade’ and resisted anyone who would challenge his view which was that the industry in the reign of ink would need more material and in more varieties than ever.

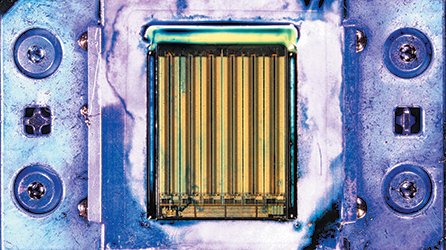

Print heads of various designs powered commercially viable printers. Scale drove prices down and made wide-format possible

Turns out, Spandex founder Charles Dobson was right. Today’s media market is witness to the fact that far from simply reaching for the nearest roll of some white staple or other, we have developed a market and appetite for materials that introduce textures into the customer conversation; we all like materials that drape obligingly or that obscure substrate under colour for example.

We have the means to print and lots of things to print upon. We have a well developed market to sell to. Is this where it ends? What is next? Where now, wide-format?

Where is this all going

Everyone has a view where hardware’s headed. On the performance side of the equation, much of the context and meaning behind the numbers you might see and which are used to propel the fortunes of a particular piece of hardware do not seem to mesh with the now evolved needs of a modern signs and graphics producer. For many smaller companies in particular, most modern printers are productive enough. That is to say they have capacity sufficient to cover what the company needs to produce but that is not the way they see it. Despite adequate productivity, if you were to ask what is needed next of a decent sample of producers, speed would be high on the shopping list of many.

Numbers, bald numbers at least, ignore the need for something that actually transcends speed in the sense we understand it. A given company might not be able to demonstrate a ‘need’ in the numerical sense, but that does not stop them wanting a printer that delivers a health quotient of ‘whoosh factor’. Get your head around that concept and it is obvious that, no matter how fast printers are, or how fast they become, they will never be fast enough. Nobody likes waiting for a printer, or, more to the point, everyone wants end-to-end performance improvements wherever they can be made. Delivering that may not actually involve faster hardware.

With ‘features’ having run rampant over the years, a printer with all the bells and whistles just does not cut it anymore. The desire is there for something with bells, whistles, and any other part of the ensemble that can be dragged in and made to work. It makes for a competitive game of Top Trumps. It used to be called ‘specmanship’. In reality, it is no substitute at all for genuine utility—that bang on target functionality, which assists in getting jobs done whether in less time, for less money or an interplay of the two.

With ‘features’ having run rampant over the years, a printer with all the bells and whistles just does not cut it anymore”

How much longer can printer manufacturers continue to raise quality, increase zero to 60 performance, and take cost out to the extent they can offer ever more aggressive pricing? It does not sound like compelling business. It sounds more like being on a four engine plane with only one engine working. All that engine is going to do is take you to the scene of the accident.

In considering what is next, or where now, wide-format, it would profit the whole range of stakeholders to consider the size of the industry and opportunity we can address to be of equal importance to the width of our printer or how fast they can hose down an acre of vinyl with all that lovely ink. Development needs to take a holistic view of the state of the industry. To do that, you need to be standing on tall shoulders.

Until the advent of viable inkjet printers, the industry’s production staple was coloured vinyl

Brett Newman is a very well-known and respected name in the wide-format printing industry. In the role he today occupies at Hybrid Services, the UK Mimaki distributor in Crewe, he has an elevated degree of oversight of what really is coming our way, only some of which he can talk about. Newman’s intuition can be relied upon too and he has a perspective to offer that adds value to any conversation contemplating wide-format. Having been in the industry long enough to remember when sign-makers wielded brushes, He is firmly of the view that a range of tools, printers if you will, is needed to cover any and all eventualities and for printer manufacturers to engage the extent of the market.

If the signs and graphics business you run is a trade supplier and its income is predicated upon the cost of a square metre and number of them you can crank out reliably, you are going to have a different view of the world that someone producing output bordering on fine art and where a major component of cost is design. Newman’s, or rather Mimaki’s, product range has something for both camps and others in between. Mimaki is also provisioning hardware that does more.

Mimaki can offer you something that might not conveniently mesh with the extreme ends the markets’ many dimensions exactly, but that delivers so much greatly enhanced capability that it belongs on your shopping list and in your future. It may even tacitly be answering the ‘where now’ question.

Versatility is key

The Mimaki UCJV series of printers is more about ‘wow factor’ than whoosh, but having said that the series’ members are plenty productive enough for most modern signs and graphics producers to operate profitably.

An object lesson in not taking things at face value, any of the UCJV series could pass at first glance as one of Mimaki’s eco-solvent printers. That is as far as the similarities go though according to Newman. UCJV revolves around a truly state-of-the-art UV ink species and that is where the differences begin and where opportunities begin to take off.

The Mimaki UCJV series defines a more capable and versatile breed of printers that helps producers do more for their customers and markets

Why UV? Ink needs to be liquid so that it can be jetted and it needs then to be rapidly dried, or otherwise stabilised, so that a useful print can be produced. One route to that end is to use a very volatile liquid carrier for the ink and evaporate it, a solvent for example. Another is to shun solvents and use something behaving more like water and let greatly increased thermal energy drive it off as is the case (in part) with latex inks. Curing the ink is your other option and that is what happens on the UCJV series. There is no concept or drying, or of drying time. The printers in the series use a highly evolved LED-UV curing regime to turn the jetted ink into a stable, dry layer adhered to the substrate. It works brilliantly.

Using LED-UV curing has enabled Mimaki to neatly sidestep a whole raft of issues that complicate life on the media front when heat, and lots of it, are a part of life. Media cockling, bucking melting, and smoking alarmingly does not happen. That, and the fact the inks are at home on substrates that do not need to be somewhat soluble mean the UCJV series has what you might call a versatile outlook. In Newman’s words: “If you want to print something on a piece of very basic and inexpensive media, the results you’ll get on a UCJV printer won’t be a let down.”

If you want to print something on a piece of very basic and inexpensive media, the results you’ll get on a UCJV printer won’t be a let down”

UV inks carry a bit of legacy baggage around and are sometimes legislated against as a result. Understand then that in the dry or cured state, inks delivered by the UCJV family are flexible and that they elongate to a useful degree. While they are not as smooth and glossy as those delivered by eco-solvent printers, we are not anywhere near the ugly piles of highly textured ink delivered by yesterday’s breed.

Where the UCJV family, or at least those of its members that are appropriately configured score, is in the sheer versatility stakes. The printer is capable of putting down layers and among them can be white. Not a watery somewhat-white white, rather a full-on heavily loaded white that packs a real punch and that plays well with the inkset’s other colours.

What this means is, applications that were very recently more-or-less the exclusive province of much more specialised print hardware, can now be dispatched on a printer that is within the means of even modestly sized businesses. Pursuing something beyond mainstream four-colour wide-format print hints at a whole sphere of innovative graphics where higher margins can be achieved and fewer competitors try to buy the customer.

Mimaki’s UCJV series puts a new species firmly on the options list of anyone looking for a wide-format printer. The pricing makes it genuinely accessible, the features and capability make it very attractive, and the way it compresses end-to-end timeframes for producing a job make it a signpost to the needs of the industry’s future.

Out in the real world where the alliance of materials and the technologies needed to print upon them are distilled into real work, you will find companies of all shapes and sizes doing what it takes to be profitable today while keeping a weather-eye on the future. What does the ‘where now’ question look like from that end of the telescope?

The Voodoo Design Works is a signs and graphics producer located close to the motorway interchange north of Bristol. The excellent communications are welcome because the company works nationally and with some very large and well-known clients. Tony Baxter is young for an industry veteran and he is Voodoo’s managing director.

Voodoo is a design-centred producer and something of an innovator. You will have seen its work on TV, at major shopping centres around the country, and in all sorts of other places too. It is a big consumer of home-produced wide-format output and has views of what is needed next.

Graphics producers never tire of new materials. The Voodoo Design Works keeps up to speed with all that is available

Baxter says: “I don’t think it’s so much a question of meeting unfulfilled need, rather building on some of the capabilities we’ve already been given. Voodoo is lucky in a number of respects. We’ve got access to all the hardware the market offers, and we’ve got great supplier relationships with the materials side of the business.

“Our hardware is a means to produce. If I could wave a magic wand and have something that doesn’t exist today, it’d probably be a machine that’s even more versatile than the ones that are out there now. A machine that doesn’t care too much about what it’s printing upon.

“We’ll never tire of seeing new materials at Voodoo. We have a plan-chest here and it must have over a hundred swatches of various ages in it. When you take digital print and introduce it to new substrates great things can happen.

“Giving places a sense of brand. That’s a stream of demand coming our way that wasn’t there a few years ago. Think about the size of that market. Where now? More things like that please. Machinery and materials versatile enough to do whatever comes through the door.”

Being there

‘Being there’ at the very genesis as a new stream of demand breaks and gaining the first player’s advantage in commercial terms is not something that happens to everyone, every day. Planning for such eventualities does though consume a lot of the time, a lot of very creative and clever people spend at work.

‘Where now, wide-format?’ is a question that materials manufacturers need the answer to, and the answer is something they need to influence. Among the most popular venues for wide-format print is the wrap. The wrap has many fathers but is a good example of an application taking a production system way beyond the design goals its creators anticipated. It is about known materials pressed to a new purpose. Hands up everyone whose sign design and production company has benefitted from the growth of interest in vehicle livery that wraps arguably have driven.

Ian Simister speaks for the materials company, Metamark. Metamark is a UK-based materials manufacturer and Simister is its sales director. His role grants him a close up relationship with the arm of Metamark that gets development done. He does not do any of the science, but he is as close to the crystal ball as its possible to be. Where to now wide-format, Simister?

Materials manufacturers have a major interest in wide-format’s development as it informs significant investments. Metamark plant expansion tells its story

“Forward! Our view of the future at Metamark is hugely informed by what we learn from some very highly qualified people we call customers. That’s how we produce materials that reflect market need.

“We’re always taking a read on design and application trends and where we see opportunities to make materials a better fit, then we get around a table and attempt to define what’s needed. That’s given us some wonderful products that have grown the market. The next generation wrap film MD-X we introduced a while back is a good example, and the colour-change material MM-CC for changing vehicle base colours is a more recent one.

“I don’t see revolution headed wide-format’s way that’s going to render irrelevant what we know today. Material that throws itself at the vehicle while the applicator has lunch or a printer that prints 5m wide output from a 50cm footprint isn’t going to be in the shops anytime soon. I see wide-format steadily building its position behind a steadily widening range of application opportunities. I am in no doubt that the coming years’ wide-format industry is something you’d know as a close relative of today’s. It’ll just be bigger, more colourful, and doing more creative things for more people than at any time in its past.”

O Factoid: Wide-format printing (also known as large-format printing) usually refers to devices that can handle sheets of paper 24 inches and wider. O

Whether you speak for a printer manufacturer, a materials producer, or a signs and graphics company your part in where wide-format is headed is anything but written. As past events prove, this industry has a capacity to surprise. What does seem evident though, is that no matter what stripes you wear, there is agreement around one thing—this industry has the capacity to grow. Our best, is yet to come.

Your text here...